|

Interview with

Remembering The 20th Century:

An Oral History of Monmouth County

|

| Sam Venti, 1998 |

Date of Interview: July 14, 2000

Name of Interviewer: Flora Higgins

Premises of Interview: Monmouth County Library,

Manalapan, NJ

Birthdate of Subject: June 14, 1914

Ms. Higgins: Good morning,

Mr. Venti, thanks for joining the Remembering the Twentieth Century project.

We ascertained that your birthday is June 14, 1914. Where were you born?

Mr. Venti: I was born

in Vineland, New Jersey. That's in South Jersey, deep down in South Jersey.

Ms. Higgins: How did

your parents happen to be in Vineland? Where did they come from?

Mr. Venti: Well, I lost

my parents when I wasn't even five years old. I have a sister who is eighteen

months older in age, and I have a brother who is two years younger than

I am, and I must have been about three years old when my mother died,

I forget. I don't remember her at all. My father passed away too, and

we were more or less orphans. I was with good people. My sister, who lived

there many years, was with the nuns in Long Branch with the Star of the

Sea Academy. She was there for quite a few years. I would say she was

there a good eight or ten years. She went to high school, she had her

high school education and everything there, graduated from there, then

she went to Philadelphia to live with my cousins, or in Camden. Well,

my uncle was from the old school, and he didn't want her to go out, and

no movies, no nothing. She met one of our distant cousins, I don't know

how close related that was, but she went over to Philadelphia and she

lived over there for a while, and she worked in the factory. I forget

what she did; a sewing factory, I think it was. And I remember taking

her up there in 1934; then she got married. She got married in the year

1937. I was married in the year 1937, too. I am so sorry to say that she

is in bad shape right now. My wife and I are having quite a time. We go

up there about every other week, trying to keep her wits together. She's

all alone, and she doesn't have anyone; her husband died and he had a

horrible death. He had cancer, started in his ear, went down to his throat,

and it was awful to see them take his jawbones out and he was fed with

tubes.

Ms. Higgins: What is

your sister's name?

Mr. Venti: Lucy.

Ms. Higgins: What did

she do at Star of the Sea?

Mr. Venti: Well, she

was raised there with the nuns. She was twenty years old when she left

the Star of the Sea to go on her own. They treated her very nicely. I

don't know what kind of things she did for the nuns, but they always seemed

to give her a few things to do. She accumulated a little bit of money

that way.

Ms. Higgins: We're trying

to get a feeling of where the people came from that came to Monmouth County.

How did your parents come to Vineland?

Mr. Venti: That I don't

know, that's where I really came from. But I do know that my mother came

from Italy. Their name is on the board at Ellis Island. My brother gets

around more than I do; he's married to a woman who wants to be on the

go all the time, and they do go all over. And they have good times; they

go to Florida for three or four months out of the year, and he has a motor

home. But that's not my cup of tea. When I go to Florida, I want to go

to a nice hotel, I want to take a shower, and I want to enjoy myself,

and we do. But we haven't gone away for two or three years because Doris

had the heart operation; since we got married she's had that stent put

in her heart. That was the last thing she had done. Before that she had

a hip joint done, had no hip. She had a clogged artery problem there.

That was a rough operation; it was in a bad spot. They had to put a bypass

up here and when you look at the x-ray the tube, or whatever it is, is

all stapled. It's just like when they did the hip. They don't sew them

up anymore like they used to, they use staples.

Ms. Higgins: Sam, what

brought you to Monmouth County and how old were you when you came, and

what towns did you live in?

Mr. Venti: Well, I lived

with the Lamb family. The Lamb family, the older people. Their daughters

and sons had all grown up and we got along just like it was my own father

and mother. They were good to us. And then when we got of age, when I

got sixteen, seventeen years of age, I went out on my own. When I say

on my own, I did some things like picking strawberries in the spring of

the year, and I'd make good money picking strawberries in those days.

I remember one day I picked to the tune of seven or eight crates of strawberries,

and I think you got like a nickel a basket for them at that time, and

I guess I made about twelve or fourteen dollars that day. It was a lot

of money.

Ms. Higgins: What town

did you pick strawberries in? Do you remember the farm?

Mr. Venti: Yes. It was

in Millstone.

Ms. Higgins: Well, during

the winter where did you work? Strawberry picking is very short season.

Mr. Venti: During the

winter I worked for two or three different people. Charlie Erwin was a

farmer on Milton Road. The farm's opposite the school there, yes, just

about opposite where the Squankum Road School is, and I started working

with him in the fall and worked there December, January, February, and

part of March.

Ms. Higgins: What did

you do, Sam?

Mr. Venti: Well, I was

working on the farm, regular farm work. The worst part I had was dragging

fertilizer for the coming year. You know they used to have people cutting

potatoes for seed. I was carting things from Chamberlin and Barkley in

Cranbury. And I used to make two loads a day with a Model T Ford tractor.

I tell you, that was hard work. When I loaded up two loads and another

load for myself, and you had to work in those days. The young generation

doesn't know how easy they have it today.

Ms. Higgins: How old

were you when you left school and then you were doing this work?

Mr. Venti: I left school

when I was sixteen years old. I was only sixteen. I was glad to go to

school because you know everybody, but I just felt I wanted to get ahead.

Ms. Higgins: Where did

you go to school?

Mr. Venti: I went to

school at Millhurst in Englishtown. Englishtown is a regional school system,

just like the Freehold one. It was in March that I left Charlie Erwin

because he didn't want to pay me. We had more or less agreed that he was

going to give me thirty five dollars a month and my room and board, if

you want to call it a room. I could look out and see the stars. I mean,

they were poor too. Farmers, they were. But anyway I got a job in the

Freehold Rug Mill.

Ms. Higgins: What was

the name of it?

Mr. Venti: A & M

Karagheusian. I never forgot that.

Ms. Higgins: What did

you do there?

Mr. Venti: Well, first

you have to practice making all different kinds of knots. Then when the

weaver had alteration to do, go from one grade carpet to another grade,

there were certain things that you had to do, like put what they call

beans, what all the jute and the cotton and then the barbets are involved,

that's the frames. So you'd be putting in barbets and keeping the material

up so the loom and the weaver, he works the front end and you're working

the back end, you're putting in the yarn but he controls the loom, shuts

it on and off.

Ms. Higgins: Were these

luxury rugs or mass-market rugs?

Mr. Venti: They were

both. They were very exclusive rugs, sure lots of times. Then there was

the cheaper carpet they made. There was a cheaper carpet and a more expensive

carpet that they made. I did that job from 1931 to about 1937 or 1938,

I believe it was. Then I had my apprenticeship. It was required that I

put seven or eight years in as an apprentice before I could handle a loom.

You had to learn, being around all this, you had to learn. You can't just

walk in there, and in a week's time say you can operate the loom; you

can't. So many things are involved. I had a pretty good career there for

a long time. Right after the war we made a little bit more money then

we made before. Well, we made a lot more, because I went weaving. Right

after the war, I became a weaver to handle the loom. Well, the pay difference

was when I started; this is what intrigues you, when I started as a creel

boy learning you got twenty-two and a half cents an hour. That's what

the start - it came out to, at that time, about eleven dollars and fifty

cents a week. And then after so many months I think it went from twenty-two

to maybe twenty-five cents an hour. I forget the steps now, you know -

it was steps. But after being there about seven or eight years, I got

weaving carpet and I made a lot more money. You made pretty decent money.

I got married in 1937: my wife, worked in the mill, also. She was what

they call a skein winder. That's putting the wool on the bobbins.

Ms. Higgins: Were they

Persian rugs?

Mr. Venti: Yes, they

were from across the pond somewhere.

Ms. Higgins: That was

a very successful factory for many years, wasn't it?

Mr. Venti: Oh, yes.

During the Depression, it was a little bit tough, but the Freehold Rug

Mill was one of the factories in the state of New Jersey that went along

pretty good. The weavers made a pretty decent salary there, and they all

had pretty nice homes on some of what you call the better streets, like

Brinckerhoff Avenue.

Ms. Higgins: Any on

Monument Street?

Mr. Venti: No. There

wouldn't be many on Monument Street, but I'll tell you where there were

true weavers. You know where the Standard gas station is, after the diner,

well you go up that street, and the first aid station is over here - there

were four or five weavers there. They did all right.

Ms. Higgins: Where did

you and your wife live?

|

| Sam Venti at his home on

Parker Street in Freehold, with his Model A Ford, 1942 |

Mr. Venti: Well, when we got

married, we lived in an apartment for only six months on Mechanic Street.

It was a practically brand new apartment; it was up over a store I think.

It was in nice shape. But we weren't there too long and then we moved

over on Institute Street. Then from Institute Street, we moved to Parker

Street. As my salary got better, we lived in better places, so to speak.

And this house that we have now, which I built myself, I built without

a mortgage. No mortgage. I was very fortunate.

Ms. Higgins: You

must have been doing pretty well.

Mr. Venti: Well,

sometimes I didn't only just work in the rug mills. If things got a

little bit slow, sometimes I used to work two days a week. We divided the

work; share the work and all that. I had learned enough about the carpet

trade. I would go out and take three months off, four months off, and

help build a house, and I made not as much as I would make at a mill at

that time, but I'm talking about after the slowdown in 1948. During the Eisenhower administration,

it was very slow then, too. I don't

know why, but it was. They always said Eisenhower was a poor president, as far

as the economy went. But I worked almost a year with an outfit in Asbury

Park that built homes all over. And at that time they paid me two

seventy-five an hour, and then that went up to five something an hour. So

I always managed. I didn't sit and cry about anything, I went to

work. And the key to the whole thing is get out and get to work

and earn your money. But the young generation doesn't want

that today.

Ms. Higgins: What kind of an impact did

the closing of the rug mill have on your life

and the life of people in Freehold?

Mr. Venti: Well, they sold some of their looms to an outfit in

New Zealand, and they wanted me to go over there and put those looms up,

because I went from weaving carpet to what you call a loom repairman and

a loom builder. And that was a good experience. About

the last fifteen years of my career of thirty-one years in that mill, I

could do work on the side. It's a lot different when you're a weaver;

you have to give one hundred percent of your attention when that

loom was running, and you better be there if something is happening, because

if you don't catch that, it's going to rip out everything, and then it's

your fault, because you weren't watching it, you left the loom running. You

would be fired. So you see they had rules that governed these

things. But I did all right after I went into loom repair. First they had me

help to build the looms. The irony of this whole thing was

the expansion part of it. I bought my house in 1947 or 1948 when I was a weaver.

Some weeks I'd bring home maybe a hundred dollars a week. Well, that's

like making a thousand today. My wife, that was my first wife, she was

very good too, helping me. We had a very happy life. My life has been

good with both women. Doris is very good woman, too.

Ms. Higgins: Was

there a union at the rug mill?

Mr. Venti: Yes, I

was the president in the last four years at the rug mill. And that's a

disaster. I don't want to put that into this interview. It is already in the

museum.

Ms. Higgins: Tell

me about your house.

Mr. Venti: It is at 65 Parker Street. The only thing I can tell you,

it's still a lot of work - you got a house you always have to work. You

always got the grass to cut, you always got the trees to trim, and you

have -

Ms. Higgins: Gutters.

Mr. Venti: And the

gutters - uhhhhhhh. Right at the present time, my son-in-law does help me

with that. I've been cleaning the gutters, but now he does it for me. I reached

that age where I can't get around up and down that ladder like I used

to. I didn't used to walk up, I used to run up the ladder, but by now I

creep along.

Ms. Higgins: What was

life in Freehold like in the 1930s and 1940s?

Mr. Venti: It was tough in

Freehold the first two or three years I was in the rug mill. I think

it was 1935, it was from the union, and the weavers, you know, it's the

one that formed the union, and I never knew nothing about a union. Well

John L. Lewis and the CIO were very, very powerful at that time, and boy,

they swept across the country. We signed up for the union, and when I

say we, I mean everybody signed up. They came around, and you wouldn't

dare say, "No, I'm not joining that union," because the weavers

were so powerful. They put me on with Jack Smith. Well, Jack, he was my

boss. And I'm going to tell you, some of them were nasty to work for.

And others were just opposite, so you had the good, the bad, you had to

learn to cope with that. I learned pretty well because I knew who was

the crab and who was the angels and you'd cope with that. You have to

make allowance.

Ms. Higgins: Do you feel,

in general, having worked and lived under both systems, that the unions

have been a good thing for the United States and New Jersey and Monmouth

County, or a bad thing?

Mr. Venti: Well,

certainly, I would say yes. But it happened to be that we were aligned with the CIO, and then in 1955

they had what they called a dispute

between the two unions, the AFL and the CIO. I'd known both of them,

but we had a lot of trouble within the CIO. Whoever got

elected president, it always seemed that they were always heading for New

York and never wanted to work. I was on the executive board

for quite a few years. And I know sometimes it was bad. Depending

on who they didn't want to work, they always wanted to cause a little

strike, you know, think it was funny. I didn't think it was funny. That's the reason I don't like to get to that end of it. Now I

gave a whole complete story to the museum, I don't know if you're familiar

with that or not.

Ms. Higgins: Sam,

what was the first movie you ever saw, do you remember?

Mr. Venti: The first

movie?

Ms. Higgins: Or

your favorite movies in the old days.

Mr. Venti: I think the first movie that I ever saw that used to make me

laugh like the devil was Laurel and Hardy. Laurel and Hardy. And then I

used to watch all those kids like Mickey Rooney, Jack, and all that. I

forget all their names, but they were a long time ago. They were the

good old days. Now this was before they had talking shows. When I went

to the movies, a mailman in Freehold also worked in the Strand theater, and he'd play the organ,

you know, boom, boom, the horses trotting, he'd make the noise like the

horses trotting and all that. Yes, I remember all that.

Ms. Higgins: Was

his name Cullen?

Mr. Venti: Yes,

Cullen.

Ms. Higgins: What

was the feeling in the community when the talkies came in?

Mr. Venti: Oh, that

was great, my goodness! When the talkies came in that was great. And I

know the first talkie I saw. It was a movie with Clara Bow. The "It"

girl right. I remember she was good; I used to like to see her, and Carole

Lombard, and Janet Gaynor; I used to like her pictures, too; I always

thought they were good clean shows. Today you get all this junk. My God,

I don't watch any of that, I can't stand it.

Ms. Higgins: What were some other fun things that you

did? Did you go to dances? What was

social life like for you and your family in the 1930s in Freehold?

Mr. Venti: Oh, yes,

we went out. In my family, my wife wasn't the type that she wanted to

be the toast of the show, or anything, you know. Some girls ask for trouble

when they go to these places, you know, they invite trouble, but my wife

wasn't that way. She didn't want to dance with this one or that one, she

just stayed a couple dances, and her sister was almost the same way, and

as I say, we had a happy life, we really had a happy life. But I have

no regrets on that part of my life, you know. And when I look back in

retrospect I say, well, I'm sad right now, you know why? My brother-in-law

passed away, not last night but the day before. He was a very good man,

very good man. And he and I were like two brothers, I mean we always did

things together, you know, and Grace, who was my sister-in-law, and she

was a good woman too. Now she passed away two and a half years ago, and

he just passed away, he died of a bad heart. His heart the last year or

so was only functioning on about fifteen percent of it. The funeral will

be Monday morning - he's at Higgins, and it's sad, you know, it's really

sad. But he raised a nice family. He had four children, and they're all

college educated and they all have good jobs. Makes a difference, a big

difference. In my day, you were lucky you got a job. There weren't any

jobs to be had.

Ms. Higgins: Do

you remember your first car?

Mr. Venti: Oh, yes.

I bought a car for fifty bucks. Fifty bucks and I ran it until I couldn't

afford the license, and that was in 1933. Yup, 1933, and we were having

trouble in the Rug Mill then, a little trouble, and I put it up with a

friend of mine, put it up in a barn, left it there. Then there was a model

T Ford. After the mill picked up a little bit, I bought a V8 Ford that

was only about a year old and it was three hundred and fifty bucks. You

could buy a brand new Ford then for about five hundred dollars, four to

five hundred dollars.

Ms. Higgins: Where

did you go in your car?

Mr. Venti: Where did

I go? I went all over. You mean where'd I drive it?

Ms. Higgins: What

did you use it for? You were working as a carpenter at that time?

Mr. Venti: Oh, I'd go

anywhere. I used it for going to work, you know, like my carpenter work

down there in Shark River Hills. But I would use the car even to go back

and forth to the Rug Mill because from Parker Street to the Rug Mill was

about a mile.

Ms. Higgins: Were

there still a lot of horses as transportation, or the trolley? Tell us about the system of transportation in the

1920s and 1930s in this

area.

Mr. Venti: Well, I'll

tell you. Before 1930 I can remember the market yard in Freehold. You'd

go down there and you might see a big truck over there. People used to

come down from New York and Newark. They'd come down here buy the vegetables,

fruits, and whatever, and maybe there would be one truck, but the rest

be all horses - jagger wagons, and some teams of horses, depending on

what they were carting. In those days in Freehold there weren't many cement

streets, and there weren't any sidewalks either. They used to have wooden

planks on Benton Street, right near the Rug Rill. I remember going to

work over there, and I had to walk on those planks to get over to the

Rug Mill. It was a big difference, an awful difference. It was hard. A

lot of poor souls didn't know how convenient because they passed on too

early; should have stayed longer.

Ms. Higgins: What

was your reaction to your first television set?

Mr. Venti: Well, I bought

mine too soon. I've had a lot of trouble with it. I bought a television

set from Wally Goldstein, who sold television sets right across from the

Rug Mill. His store was there. And it was a Dumont. My wife was friendly

with Mary, can't think of her last name, but anyhow this fellow's name

was Bill Oaks; he worked for Willy Goldstein setting up these sets. Every

other night, regular by clockwork, he had a Dumont going. And I'll tell

you, that was an expensive set. I paid five hundred bucks at that time.

At that time it was five hundred bucks, and like a fool I paid Willy Goldstein.

I think I paid him cash for it. I went and gave him real cash. Bill, who

works for Wally, phoned and told me he had a set, also, and he had a lot

of trouble with it, but he didn't want to tell Wally, because he would

lose his job. He worked repairing sets. But his wife and my wife were

good friends, and he used to come over and he would fix my set and he

wouldn't want to take no money, and stuff like that. So it was a good

thing we had friends. We had a lot of friends that helped us out too.

Ms. Higgins: What historical events do you feel have had the

most impact on your life? You were born at the start of the First World

War. Of all these historical events, what do you think have had the most

impact on your life?

Mr. Venti: There's so

many, it's hard to say. I will have to do a little thinking on that one.

Automobiles is one of the things, the other is to see how they used horses

to do farming. You'd ride up the road and see the barnyard had fifteen,

sixteen horses which they used to farm. You look up the road now, you

see no horses, and you see one or two tractors that do all the work sixteen

horses done. Another thing: I just came to reality to think about this

in the last seven or eight years. If people want to farm they better know

something about farming. When I say they better know something, I mean

they better get educated, because you cannot farm unless you go to college.

For example, everything has to have a certain type of fertilizer. Different

plants have to have a different strength. A friend of mine, George Rue,

lives up in Upper Freehold Township, and I've asked him two three different

times about different things: about how this kind of grass grows, what

to get to get rid of what I don't want. I've learnt a lot about that too.

If you want a beautiful lawn, you'd better lime it. It's best to lime

it in the wintertime, because the snow takes it down, and it doesn't blow

away. All these things are what this farmer told me about. It's amazing

how many different kinds of ingredients there are for different things,

too. Do you remember the DiFidellis?

Ms. Higgins: No.

Where were they?

Mr. Venti: I'll tell

you where they were, and they're still there.

Ms. Higgins: Where

do they farm?

Mr. Venti: I think they have

four acres of ground, each with a big house on 537. They were there in 1925, I

guess. But I think they're pretty well gone. The younger have ones left, and they

have given up farming.

Ms. Higgins: I've interviewed enough old farmers in this area to know that

farming is a very hard way to make money, and getting harder all the time for the

family farmer.

Mr. Venti: Rue farms all

the ground, he farms

maybe thousands of acres. But I see he's cutting down

this year. But he grows two crops off the same ground, see. In the fall, they plant barley, or they plant

rye. That stuff all harvests in early June to July. Then they turn

around and plant the soybeans. That's getting two crops. And that's

the only way, he says, you can survive. Irrigation is another very

important thing for a farmer. If he wants to stay in business he better

have some water, or get water and irrigate, or he's taking an awful

chance. When I see these things off in the West, like this milk

situation, that's pitiful. The middleman makes all the money. The guy

that's doing all the hard work, taking care of the cows and all that business, he's

hurting, he can't get enough money. I think they get less than a dollar for a

whole gallon of milk. A whole gallon, and they get less than a buck. Stores

get three. Now they're going up to about three forty.

|

| Sam Venti and Ann Lamb (Smithburg),

1932 |

Ms. Higgins: Please tell me about the medical practices when you were growing up.

When you got hurt or sick, where would you go?

Mr. Venti: Well, when

I was a kid, when I lived with the Lamb family, they had us in the hospital,

my brother and me, and they took our tonsils out. Today they're not so

interested in taking those tonsils out. Doctors used to come to the house,

too; if you called them up, they'd come to your house. And my wife and

I went to the doctor last Monday. We go in the same room because we get

blood work done and all that. The doctor didn't come in for another twenty-five

minutes. We never got out of that office until quarter to eleven. And

it's that way all the time. They're all doing that. Now we go to Dr. Lario.

I don't know if you're acquainted with him or not. He's good, but he's

in bad shape right now because he's having a cornea transplant, and it

was a waste of time us going down there because he didn't want to do any

blood work. He said, "Wait until I come back in September. When I

come back, I'll take blood and we'll check you."

Ms. Higgins: Sam, after

you worked for the Rug Mill, when did you come to the Monmouth County

Library? I understand that you were employed by the Monmouth County Library.

Tell us about the early days at the library.

Mr. Venti: I came to

the library in 1962 in the spring of the year. I took a test in Trenton.

Well, I'll tell you how I got here. I was president of the union the last

four or five years. The reason is because I used to fight with the AFL-CIO

in New York. When the company made the announcement that they were going

to move, they promised that they would handle the situation, do this,

do that and do the other, and I called my executive board together. Some

wanted to get a lawyer, some didn't, so I called another organization

up and told them how everybody felt. So a gal by the name of Pattings,

who was a lawyer, came down and said she was going to do so much, but

they started moving all the equipment. After the equipment was all moved,

I was after them, but all they wanted was the money. And that's what we

got out of it. After fighting and arguing so much, we finally settled

for anyone who had twenty-five years of service, and they got two weeks'

worth vacation severance pay. Now that was chicken feed. But I have a

lot of papers home that I gave to that gal down there, a nice gal, at

the museum, like what the pay was, and different things like I'm telling

you. The pay was eleven dollars and fifty cents a week for krill boys

who started working for Karagheusian. Then on the other hand, when you

were a weaver you were at the top. Then when Mr. Karagheusian died, everything

went to pieces. There was only one other Karagheusian, he was their nephew

Charlie, and he wasn't interested in that rug mill at all. He had a yacht

down in Brielle. He lived on the yacht- he had housekeepers and everything.

But that didn't help us. John Bikler was the head of the state unemployment

office in Freehold. When you have a union, the union can appoint anyone

to represent a worker and work on any claim that the worker may have against

the unemployment office. Well, most of the time, the person himself caused

the problem but you can't tell them anything; I've represented many different

ones. Every time I was honest when I represented them. This gal Mary,

whose last name I forget, had a problem. I said, "Now wait a minute.

You tell me they objecting to paying you for the last two weeks?"

But this was the reason: she was told to come in for her checks every

two weeks, but Mary told the woman at the window, "Oh, I got to go

to Florida for two weeks because I'm not working." The woman says,

"Oh, that's nice." Two weeks when Mary came back to sign up

to get another check, the woman said to her, "Oh no, we can't pay

you." Mary says, "What do you mean?" and she comes busting

to me. She didn't tell me all the story, so I go up there and I learn,

and I say, "Mary, you're not honest with her yourself. Are you that

dumb?" If she had not said anything, she would have gotten her money.

And that happens all the time, all the time that happens. That's only

just one of the things that happened. They used to curse me. Some women

can be tough with language. You wonder where they pick it up. I'd been

sworn at a lot.

Ms. Higgins: When did

you come and work for the county? Did you have to take a civil service

exam?

Mr. Venti: Yes, civil

service. So I just about made it. Seventy-one or two I scored. So I went

to work, I think it was as a bookmobile driver. Remember Don Price? He

was the bookmobile driver. He died almost a year ago. Anyway, poor Don

was a nice guy, but he was so careful. I don't know how they got along

with him like they did, but he had a lot of different women that rode

on that bus with him. He was a good driver, but he was always sick. I

don't know what was the matter with him. Got a mental problem. And I got

involved in that too. His father and mother were dead and gone, and my

wife got involved. I'd call her and say, "Look, take Don down to

the hospital." He was dealing with some psychiatrist, and whenever

he got real bad, he went to the hospital. Did you ever meet Julia Killian

who was the director then? Anyway, she was my boss. She was all right.

The library was not in very good shape. She didn't want to leave the library.

She brought people in the library. Anna Wang knows this too; she brought

people in the library because she thought they were friends, so she gave

them a job and stuff. This was a woman I'm talking about. Next thing you

know Julia is out. And during the War she was with the Red Cross, she

was some kind of official at the Red Cross, and she was a brave woman.

I'm a firm believer, don't kick anybody when they're down, if you can't

help them, get out of the way. She was very critical of Jack Livingstone,

her successor. Jack was a good man. He was fair with me. He made this

library what it is today.

|

|

|

Monmouth

County Library Bookmobile |

Ms. Higgins: Tell us about a day in

the life of a bookmobile driver.

Mr. Venti: Sometimes

they'd go to spots that weren't doing anything. You probably heard that

too. I don't like to get involved with it, but I used to say about the

different ones, "Why are they going up on Norfolk Farm? There's only

one woman who comes up there. You don't need a big bookmobile dragging

all those books up." But I never said anything one way or the other.

Livingstone was smart, he knew what he was doing. Jack, he gets credit for what the

library is today. He was fair with me. He and I got along good because

he wasn't afraid to work either. The first day he came to where I was working,

the library had that place over on Marcy Street. They were getting ready to

move, and we had

thousands of boxes of books. We had to sort them. I drove a small

bookmobile, I liked that, and it was a good job. I used to drive the

school bookmobile to the schools. They used to change

all their books, and I got along good with everybody. Everything went

fine. If something happened to the bookmobile, I'd fix it myself. I

worked on motors and stuff. So Jack called one day and I had the

carburetor off the bookmobile at the school, and he came up and he says,

"So what's the matter?" So I said, "I'll tell you what's

the matter, Jack, I went down to the gas pump, and we found out there's

water in the gas and this thing won't start. So I drained the tank. I

saw a tactic to get the carburetor off to get the water out of the

carburetor." He said, "Well, I'll be." He couldn't get

over me. He says, "I'm going to put you head of this equipment

around here." And he did.

|

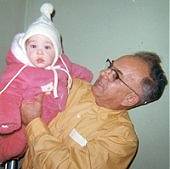

| Sam Venti with his

granddaughter, Mary Aurora Kress, June 1969 |

Ms. Higgins: Sam,

I'd like to ask you to talk now to future generations. We

are hopeful that future generations will be listening to and reading

this interview. What wisdom would you like to pass on to them? What

disturbs you most about the world today? What are the good things

that you think we should capitalize on?

Mr. Venti: First

thing that I would say to the younger generation, and I know

they won't like this - don't start smoking in the first place. That's

number one. Number two, get away from this business of running to the

saloons. And the rest will take care of itself. And always be

truthful - if you do something wrong, don't be afraid to admit that you

did it, because you're a bigger person when you admit it, and you're a

smaller one when they catch you in a big lie. These are my words to this

generation today. And work never killed anybody. Work always helped. And

it even helps me in this day and age, and if I

just sat in a chair like a couple of my friends have done, I would be in bad

shape. Twelve years ago, this guy I know decided he wanted to stay home. He watches all the

shows and movies all day long into the night. His wife is going crazy. She was working,

but she was sick of working so she quit, but she exercises. But Joey's in the institution in a wheelchair. She had to put him in

there because she couldn't take care of him.

Ms. Higgins: Well,

you are certainly in very good shape.

Mr. Venti: When you feel pains just kick your leg around a little bit.

You got to keep

it going.

Ms. Higgins: I

wish you a very happy belated birthday and many happy returns. And

we appreciate this interview very much.

Mr. Venti: That is

what my advice to the young kids is. It is the advice that I will preach

at.

Ms. Higgins: Good

for you, Sam, thank you again.

|