|

Interview with

Remembering The 20th Century:

An Oral History of Monmouth County

|

| Mr. May with friends

celebrating the last dinner on the Titanic |

Date of Interview: August 10, 2000

Name of Interviewer: Douglas Aumack

Premises of Interview: Mr. May's home, Ocean Grove, NJ

Birthdate of Subject: August 4, 1939

Mr. Aumack: How did

you come to Monmouth County?

Mr. May: I was

born in Long Branch in Monmouth County and I've lived here all my life,

so that's how I came here.

Mr. Aumack: What

hospital was it?

Mr. May: It was

Hazard's Hospital, but is now Monmouth Medical Center.

Mr. Aumack: How

small was that hospital?

Mr. May: I

imagine it was quite small; of course I don't remember because I was

small myself. But I know from my mother telling me that it was a small

hospital and Dr. Hazard was in charge.

Mr. Aumack: How

long was your family here before you were born, do you know?

Mr. May: My

family goes back in Monmouth on the Covert side; the

family home was in Wayside, and I don't know how many years they were

there, but probably from the early 1800s. Maybe even before then. There's a

Methodist Church on the hill in Wayside that seemed to be the church of all the farm families in the area

and we're still there. I was just there with my sisters,

up visiting the grave sites; her husband died not too long

ago. But we're there, and it's interesting when you come from a small

town like this and you've stayed in the area. I had a friend who I

went to school with, who was a classmate of mine, and years later, I

guess it was about thirty years later, I saw her. I had the Pine Tree hotel here in Ocean Grove, and she sought me out and said,

"Do you know we're related?" Well it was that up on the hill in that cemetery,

that she found out. I guess the families

intermarried. But that's the one side of the family, how we got the

connection with Ocean Grove here, where I am today. My great grandfather

was a baker for West Point and he moved from West Point about the same time

Ocean Grove was founded, and opened a bakery

here. I don't know too much about the bakery, but I do remember my

grandfather showing me pictures of himself as a little boy, on the

streets of Ocean Grove with a goat cart, selling bread. And then my

grandfather had a big horse drawn truck and it said "No flies on

the bread, bury the name of Magathan." So he came down here and the

rest is history. My mother was born here; my grandfather had married into the Coverts,

the family out in Wayside, so we've been in this area ever since. We go

back a long time here. Probably the Coverts side goes back a lot longer

then the Magathan side. They came over before the

Revolutionary War and they fought with Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys.

But the family member who came first eventually moved west with the land grants.

They all moved to Kansas. That was a part of the family I

never knew about. I just thought they came from Scotland with my great-grandfather coming over.

One of the members of my family did

research and found out most all of them are out in Kansas, including my

great grandfather, who was born there. He worked at West Point and then

came to Ocean Grove. So he didn't come from Scotland, he came by way of Kansas! I've never met the families out there. I have to go out some

day. My cousin has been out.

Mr. Aumack: And

this is the Magathans?

Mr. May: Yes,

this is the Magathans. It was MacGathan when they came over, and of course

they changed it when they entered the country to Magathan.

Mr. Aumack: So who

went to West Point? What was his full name, do you know?

Mr. May: Yes,

John Magathan.

Mr. Aumack: Do you

know when he graduated from West Point?

Mr. May: He

didn't go to West Point, he was the baker for West Point. I guess he had

been in the baking business out in Kansas, and his family and he got this

job in West Point. And then from there he moved to Ocean Grove and brought

his four children with him. My grandfather was one of them.

Mr. Aumack: Now

when he sold his bread, was it more door to door while having his store

at the same time?

Mr. May: I'm not

sure, I really don't know. I just remember seeing pictures of the old bakery truck, and my grandfather

obviously went from door to

door because he had the goat cart with the bread in it.

Mr. Aumack: So he

first used a goat and then a horse?

Mr. May: Well, my great grandfather was the one that had the wagon. My

grandfather was a little boy and he had the goat cart.

Mr. Aumack: Do you

remember the name of the bakery?

Mr. May: No I

don't. I remember seeing on the truck "No flies on the bread during

the name of Magathan." It was kind of interesting.

Mr. Aumack: It was

an advertisement as well as a sign.

Mr. May: Right.

That was printed on the side of the truck. I don't know too much about this, my

grandfather wasn't too into the history of the family, so what we

learned was when somebody did research in Washington, DC.

Mr. Aumack: Now,

what is your earliest memory of childhood growing up?

|

|

|

Mr. May at age six, after

winning a contest

|

Mr. May: I was born in 1939,

and I

guess by the time I was two or three I remember my father went into the war. He was in the Navy,

stationed in the Pacific. I had sisters. You met one of them, I

guess when you came in, but they're ten years older than I am. And

they're identical twins. My mother had the twins and then me ten years later,

and I'd say I was about two or three years old when my father went into

the service. So my earliest recollections are just being in that house, and the

blackouts. You know during the war, when you're a little kid, you

don't know why all the lights are out, and they pulled all the shades

down, and so on and so forth. But we had the blackouts in case we were invaded or something,

the invaders wouldn't see any

targets of lights and so on. I do remember that we lived in Shrewsbury

Township, which is now Tinton Falls. I remember

the airport too, and that was neat, because there was an airport in Red Bank. In fact there's a restaurant called the Airport Inn on Shrewsbury

Avenue and one of my earliest memories of the years we were on Peach Street

and we could watch the planes taking off from the Red Bank airport. I

remember just sitting on the porch and we used to have a little game

guessing what color plane would come up next. That was kind of fun. But

the dirt road and the open land, you know this wasn't farmland, it was

open land across the street. I remember going to school in Tinton Falls. I

remember kindergarten, because it was all day. You went all day and

you had a naptime, you slept and so on. It wasn't like now when you go for two

and a half hours and you go home. It was all day kindergarten. I was

only in Tinton Falls in the school there for one year, and then we moved

to Shrewsbury. My mother moved us there. She had a rough time of it

because my father was gone and she had three kids, and the landlords wanted

to either sell the house or use it for themselves, so we had to get out. She had to move the family herself and

relocate in Shrewsbury.

Mr. Aumack: So your

father passed away in the War?

Mr. May: No, no. But this

move happened while he was stationed in the Pacific.

Then when he got out, of course, he was able to do the things that

needed to be done with this house that my mother had purchased. It was very

rough, it was right at the end of the Depression, and then from the

Depression we went right into the War.

Mr. Aumack: Why did

you move to what is now Tinton Falls, from where were

you, in Long Branch?

Mr. May: We didn't move in

Long Branch. I was

only born there. We lived in Eatontown.

Mr. Aumack: Why did

you move from Eatontown to Tinton Falls?

Mr. May: Because

the house was available. My

mother was looking for a place to rent. We were there for a few years,

and when that house was no longer available, then she had to make the move, and

she had to make it without my father because he was in the service. We moved to Shrewsbury.

I think they had that place for about forty years. I grew up in Shrewsbury. I moved there when I was

five. We never moved again, and as I say, they lived

there in the same house for about forty or more years.

Mr. Aumack: What

types of planes were at this airport?

Mr. May: They

weren't military planes. I don't remember too much because I was only

about three or four years old, but I do remember the airport. I remember

one incident. I guess I was always

the kind of kid that got into things, and I just decided that I was going to

fly an airplane. I was about four. Somehow I got into the

airport, where the planes were, got up inside the plane, was in the

cabin, and I was up there having a ball, waving to people. They were

having to search for me, and they found me in the airplane. School busses took you to school and

brought you home. I was only there one year, but my sisters were

older, and I remember sometimes the bus would wrap around and stop near

my grandparents in Eatontown. Now we were living on Peach Street off Shrewsbury

Avenue there, what is now Tinton Falls, and there was a bar at the end,

which is now a restaurant, the Airport Inn. The bus used to stop

there, and now that I look back, I guess the bus driver just stopped there for a quick

one after he did the rounds. But I had been with my

sisters once or twice, and they went to my grandparents in Eatontown

while he was bringing the bus back to where they parked it. So I told my

mother, "Mom, I'm going away," and she said,

"Where?" and I said, "I'm going to see my grand mom."

And she said, "Have a good time," and said goodbye. Well, I got on

the bus, had the bus driver convinced that that's where I was supposed

to go, and if he hadn't stopped for a drink, I would have been at my

grandmother's. My father and mother were just frantic, but I was up on

the highway on the bus waving to her. She asked, "What are you

doing in there?" And I said, "I told you I was going." I remember getting lost

once in Red Bank. I was sitting on the curb,

and I wasn't really upset, I was just frustrated because I didn't know

where she was. A cop came over and said, "What

are you doing here little boy?" and I said, "I lost my

mother." So he made the search and found her. Then we moved to

Shrewsbury, and most of my memories are from Shrewsbury.

Mr. Aumack: What's

your fondest memory about Shrewsbury?

|

|

|

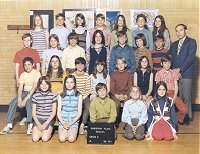

Mr. May at school in

Shrewsbury

|

Mr. May: Shrewsbury? I was there from five until college, so I have a lot of

memories of Shrewsbury. I remember

in the fifth or sixth grade and having this teacher who was just

wonderful. Everybody dreaded her. She had been there for years, and she

had taught this one's father, and that one's grandfather, and so on, and

she was very strict, but she turned out to be a real asset for me because

she really got me on to school. Just that one person.

Mr. Aumack: Is that

school still standing?

Mr. May: Unfortunately, no.

That school was a wonderful, wonderful school, it was built in 1908 and

its façade was wonderful. It was a beautiful classic school. Mind you,

after I left Shrewsbury, I went on to college, and I taught at Little

Silver, and I'm very much interested in the teaching profession and am

very involved in it. If I had stayed in Shrewsbury, I probably would have

gotten more involved in saving the school, because the people in the community

came up to vote in Shrewsbury two or three times. The people voted not

to take the school down, but the board wanted to expand, so it went ahead

and got permission from the state to level against the wishes of the community.

So I mean it was unfortunate historically, because the piece of architecture

was beautiful. My twin sisters were a big part of my life because they

were ten years old when I was born, and I became like the living toy to

them, and so they were always interested in what happened to me, and what

I did, and so on and so forth.

Mr. Aumack: They

were two babysitters and two guardians.

Mr. May: Right,

but it's a different experience when they're identical twins because the

two of them are just -

Mr. Aumack: What

makes them so -

Mr. May: So unique?

Well, they're so much alike and they're so different. So close, yet they

wanted to be independent. They were the kind of twins that didn't want

to be exactly like the other one and dress like the other one, and so

on, looking for their independence. Boy, they used to tease me. My family

name was Buddy - "Do you want to come here, Buddy? Come over here

with me." And I'd go over there and the other would say, "Oh,

you don't want me anymore." You know, then they would drive me nuts,

back and forth, back and forth. I think that just growing up with that

has made it possible for me to deal with different factions, or to be

aware not to neglect this one because I learned quite a lesson from them.

I learned how to deal with the demands that are made on you from different

sides. But they're both in Florida.

Mr. Aumack: Describe what it was

like living in Shrewsbury.

Mr. May: I don't know what the class size is now,

but in my graduating class I think there were only seventeen

kids. Like everything, Shrewsbury grew, but it was just a nice environment to grow

up in.

Mr. Aumack: Did a

lot of people know everyone else?

Mr. May: In Shrewsbury? Yes,

and I was rather involved in a lot of things. I was in the Boy Scouts,

and I was in different choral groups, and we put on plays. I remember

this teacher in particular, Helen Lang, that I had, I don't know how she

did it, but I had her for fifth grade when she had fifth and sixth. As

a teacher, I know having just one grade is difficult, but she had

fifth and sixth. She was so organized she'd teach a lesson in fifth, and

then she'd give you a reinforcement exercise, or whatever, to start on,

then she'd go teach a lesson in sixth. We were in the same room. Two rows

of fifth grade and two rows of sixth grade. And she'd go back and forth

all day. And yet, with doing that, she'd still have time on every Friday

for the combined class to have a talent show, or program. It wasn't like

it was a special one, but every Friday people would get up there who wanted

to play their instrument, or they would form a singing group, or recite

poetry. About an hour a week was set aside for that. And that was just

wonderful. We didn't have any time in class to prepare for it, but we'd

prepare after school. We had a singing group, three or four of us, and

we'd get together and practice our songs to sing on Friday.

Mr. Aumack: How

many kids did she have at once?

Mr. May: Well,

as I say, there were probably about seventeen in my class, so she must

have had thirty to thirty-five kids in two different grades.

Mr. Aumack: But

they were all in the same room at the same time.

Mr. May: Yes, two or three rows of one, and two or three rows of the

other. Just

physically getting all those kids in was a problem. I don't know what the sixth grade

was, I just remember what my class was, so maybe it was a smaller sixth

grade. I know we had seventeen, so maybe they had thirteen, I don't know.

Mr. Aumack: It just

boggles my mind how she would teach two classes at once. How did she do that?

Mr. May: Well, I know

how to do it because it is my field. It's not easy. And she was really

good at inspiring kids in that kind of environment; she really was good.

There was a little penny candy store we used to stop at. It seemed like

forever, but it was probably only three blocks in the other direction

towards the Old Christ Church and the Allen House. And I remember the

store was between school and the Allen House. I remember once in a while

venturing up there for ice cream. Lovett's Nursery was just all fields,

it wasn't a mall. Between Red Bank and the Old Christ church, going towards

the place on the left hand side, there was Lovett's Nursery, which has

been leveled now, and has housing developments on it. When I was a kid,

it was all open fields.

Mr. Aumack: How has

Shrewsbury changed?

Mr. May: Well, it's

just become more populated, but it's still a very nice community. But

having taught in Little Silver, I have ties there. Also, because of my

involvement in the teaching profession, I represented the teachers from

all over the county as the president of the Monmouth County Educational

System. There were ten thousand members and about fifty or fifty-five

locals. But Shrewsbury was very close to my heart because I grew up there.

I never got very far, you see. I grew up in Shrewsbury, went to Red Bank

High School, came back and taught at Little Silver; it's all within a

couple miles. My whole growing up and business life was in that area.

My ties are here in Ocean Grove because of family. My grandfather's sisters

stayed here.

Mr. Aumack: Now

after grammar school, where did you go to high school?

|

|

|

Mr. May in high school

|

Mr. May: We went

to Red Bank High School. We were tuition students then, it wasn't

regionalized. We were tuition students from Little Silver and

Shrewsbury. It was a big change for us because we come from about

seventeen kids in my class to a big high school setting. We used to

catch the bus to the high school.

Mr. Aumack: How

many people were in your graduating class?

Mr. May: From

high school? About one hundred and eighty.

Mr. Aumack: How big

were the classes?

Mr. May: In high

school? It varied. The gym classes were always huge, but I don't

remember class size being a problem, I don't remember being jamming

in, so I would say the largest class was twenty-five or thirty students.

Mr. Aumack: When

your mother or father wanted to go shopping for food or clothing, where

would they go?

Mr. May: Red Bank was the

closest. Even today, Red Bank has remained a lovely area. I went to high

school there, and when we went to town, we went to Red Bank. There was

the butcher shop there, there were different places there, and places

to shop for clothing, and various other things you would need. However,

I remember going about twice a month to Long Branch. Long Branch was a

bigger city. Red Bank was small, and Long Branch at the time was a very

nice city, and my mother would go there, two, three or four times a month

to shop. But the big place was Asbury Park. That's why it breaks your

heart just looking at it today, because it was just magnificent. Maybe

once a month we would make the big time and we'd go to Steinbach's in

Asbury Park, and Canadian Furs, and Tepper's, and all of the fine stores

that were there. Interestingly enough, in later years when I was in college,

I worked in Asbury Park. I worked there before, during, and after the

riots, so I could really see what happened to Asbury Park. I was there

at sort of a critical time. Just like really in Ocean Grove. When

I had the Pine Tree Inn, the hotel here in the Grove, it was before, during,

and after the gates coming down and opening up Ocean Grove. But going

back to where we shopped, Asbury was the big place.

Mr. Aumack: What kind of store

was Tepper's?

Mr. May: Tepper's was

sort of a gift shop, linens; it would be comparable to your bigger department

stores only it was small, but it carried fine items.

Mr. Aumack: Do you

remember when the roads were paved in Long Branch and Shrewsbury?

Mr. May: As far back

as I remember, they were all paved. All the main roads, at least. In Shrewsbury,

the house I grew up in was at 40 Laurel Street. Laurel Street went up

to Thomas Avenue, I guess it was, but anyway it just ended, but then when

they put in the development, they continued the road up. It was an all-wooded

area when I grew up; it was just a road that went around like a rectangle

with houses on it, and the rest was woods behind it, but of course it's

all developed now.

Mr. Aumack: Did you

ever use any public transportation to go anywhere?

Mr. May: All through high

school. Because we were tuition students, we didn't have the yellow school

bus pick us up. We got to the high school using a bus pass, so we used

the public transportation for that.

Mr. Aumack: Do you

remember what company was in charge of that?

Mr. May: I

remember Borough Busses; it might have been that.

Mr. Aumack: Let's

go back to Asbury Park. When did you start working there and what was your

job?

Mr. May: I went

to college in 1958 -

Mr. Aumack: What

college was that?

Mr. May: Montclair State

College. At that time I had two options: first of all, I came from a family

where you felt loved, and it didn't matter what you did. So there wasn't

the emphasis to succeed to be loved. It wasn't the push, and so on. I

really had a very interesting life because I was free to do what I wanted.

My mother and father just let me explore everything and anything that

I wanted to do. My sisters were a big encouragement for that freedom,

too. I know the sister you met here, Evelyn, used to say, "There's

no such word as 'can't.' If you want to try it, just do it." So I

grew up that way. I'd always thought I'd want to be a teacher, but I also

thought that I'd like to go into business, and I didn't quite know which

field to go in, and I wasn't under any pressure to go into either one

of them. So I had applied to NYU to study retailing. In fact, there was

a store in Red Bank which was a very fine men's clothing store then. It

wasn't Roots, Roots came later, but it was J. Kridel's. Kridel's was the

big clothing store. Kridel's had a scholarship and I got the scholarship.

And as I said, I didn't have the pressure like, "Oh, you got a scholarship,

so you have to go." But I did get the J. Kridel scholarship. It was

four thousand dollars, a thousand dollars each year. Today that seems

like nothing, but at that time one thousand dollars paid for a whole year

at NYU. I remember thinking I would be probably living in the Village,

and my expense would not be the college, because I had the thousand dollars,

but it would be for the room and board. I'd have rent and so on. So I

also applied to Montclair. Well, it was a state school at that time, and

believe it or not, the tuition at Montclair was only ninety-six dollars

a semester. So at Montclair, the whole year's tuition was less than two

hundred dollars. But I decided to go to Montclair because I could go in

for teaching, and I could also major in business. So I entered Montclair

as a business major, with social business minor, and then went taking

courses in education. I majored in accounting, so I could either venture

out in accounting or into teaching of business. But that wasn't to be.

My college career was from one thing to another.

Mr. Aumack: So you

did a lot of exploring.

Mr. May: Oh, I certainly

did. I had a speech class in my first semester as a freshman. The kids

wanted me to be class president, well I turned that down, thank God. I

turned that down, or I probably wouldn't have made it through the semester.

But, I also had that speech class, and I really liked the speech class.

Then the head of the Speech Department called me into his office and said,

"Phil, we'd like you to be a speech major." Well, I really liked

speech, although I never thought about going into that. It was dramatics

and speech therapy. They wanted me to do the lead in the school play,

Our Town. Well, I just felt that I should do some background work,

I was the new kid on the block, and that should go to a junior or senior.

So I turned it down, which is kind of weird when I think back on it. Most

kids would say, "That's great," but as a freshman, that was

my view on things. Also, I was rushed for three or four fraternities.

It was like a madhouse. I went from the little town of Shrewsbury and

the hardest to get into fraternities thought they were the top dogs and

so on. I finally joined a service fraternity in college. So I was in a

fraternity during my first semester. I should have just broken away and

become a speech major. But I just had this idea that I would always have

business as an ace in the hole. So then I was trying to complete two majors,

and then with social business minor, you had to minor in business also.

So I was going to school in the summers for that, and I got to the middle

of my junior year and decided that I really wanted to go into speech.

The Speech Department had been after me. Well, then they had a problem

within Montclair, in the departments. The Business Department didn't want

to let me go. I thought it would be an easy transition, and it would have

been as a freshman. The head of the Speech Department was delighted that

I was making this change, because he had been hoping that I would do that

all along. When the business department found out about it, well, they

were at each other's throats over what department I was going to go in,

and I remember the Speech Department head calling me in and saying, "Phil,

we'll help you get into any college in the country in speech, but there's

so many problems here within Montclair with the departments that we can't

take you." So I thought well, they're not going to do that to me,

I've always been independent. I also had an art class. Now I never

had any art background at all, whatsoever. Shrewsbury did have an art

teacher, but the program was very limited. In high school, I never had

a thing in art. At Montclair, I had this art appreciation course which

I really liked. The head of the department was Dr. Calcia. I thought they're

not going to make me stay in a department, so I went to the head of the

Art Department and I said, "What could I do to become an art major?"

She asked for the background; I said I had none. So I was like an experiment,

because I was fresh and new, with no preconceived ideas of what should

be done. She couldn't believe it. She said, "All I can tell you is,

if you're in the middle of your junior year and you're willing to switch

majors into a major you know nothing about, then I will accept you into

the department." The next semester I didn't register for business

classes. I was not a speech major. So as far as I was concerned, I wasn't

any major. When I talked to the head of the Art Department, I told one

of those little white lies. I said I didn't have a major. I finally got

through to the Dean and I told him that I didn't have any major and he

said, "But you've been here for two and a half years. Nobody goes

here with two and a half years without declaring a major." And I

said, "I don't have any major right now, but I want to be an art

major, and Dr. Calcia will take me into the art department." And

he said, "Well, you've got to get a major. So, if she's agreeable

we'll just send you to the Art Department." So I became an art major.

I had to make up three years of all of the classes, and in art you had

to minor in art as well. So I had all these art classes. It was a whole

different field. Then the head of the Business Department found I hadn't

been coming to class. Well, I didn't have any business classes. He said,

"I haven't seen you in class." And I said, "No, I'm not

a business major anymore." And he said, "What do you think,

the Speech Department will have you?" And I said, "No, I'm an

art major." He sat down and said, "I don't want you to go, you'll

be a wonderful business teacher, and I think you'll be great." And

I said," Why didn't you talk to me about this before? It's too late,

I'm an art major, but I'll continue as a business minor." But he

didn't want that, it was either all or nothing. So I finally graduated

with about five and a half years of credits, from speech to business,

and finally majoring and minoring in art, and my first job was in Wall

Township as an art supervisor. I had sixty-five teachers working under

me, and I was the new kid on the block just entering the teaching profession.

And I worked with kids, also. I did demonstration lessons and worked with

them on follow-ups.

Mr. Aumack: So what

was your degree as?

Mr. May: Well,

it was an art major with a business and speech minor. I can teach business and

speech from seven to twelve, and art K to twelve. My first job was as an art supervisor, but I

really love teaching. And I love working with the kids, and not just

doing demonstration lessons. I decided I wanted a class for myself.

So I applied for jobs in elementary education, but even with all those

credits, I didn't have elementary certification. But I got a job in Bergen

County, in Glenn Rock, one of the best schools in the state. I

taught in Glenn Rock for two or three years, even though they said you'll never

get into Glenn Rock because there was such a wait line and it's such a

wonderful system. You'll never get in there. And I didn't have

certification. With all certification I had, I didn't have elementary

certification. But they were extremely

professional. They didn't just look at credentials, and so on and

so forth, they interviewed me, and then they came down and they watched

me teach, and not only the principal, but the curriculum coordinator,

and so on. They paid Wall Township for the day for

me to come up to look at their system so that I would make sure that I

was making the right decision. They took me around the district, introduced me

to the

superintendent, took me out to lunch, and had an extremely professional way of

handling it. And even without certification I got the job. But I had to

get elementary certification, which I did. I was there two years, but when you

get the sand in your shoes, you just can't leave the shore, and I just

wanted to come home. They were so delighted with me. I'll never forget

they called me in to the office. There was the superintendent, the

principal, and the curriculum coordinator. Although I'd taught there only two,

maybe three years, they offered me the job of principal. This was before there

were contracts for

teachers. They could do what they wanted,

and offer the salaries that they wanted. But they called me in and said that

they were offering me the job of principal. They were offering me the job of principal of their junior

high, and they would pay for all of my masters degree for

certification in administration. They

groomed you for the position, it was like a picture book, the way they

ran that system. The current principal was leaving in two

years, and I would take over the school in two years. I was flattered. And it's funny how

some things you remember. I remember saying to them, "You

know, I don't want you to feel that I'm ungrateful, but I got in this business to

teach, and I don't want to leave the

classroom." It was such an emotional thing to be

offered this position with all expenses

paid, and then to turn it down, but I had said when I leave, I'll leave

the classroom. And I did. I left there in a year and I came back home. Then I taught in a ghetto school for

three years.

Mr. Aumack: What do

you mean a ghetto school?

Mr. May: Well, I

couldn't understand why I wasn't getting calls, because there was a

teacher shortage then, but I wasn't getting calls from the

districts that I applied to down here. I didn't plan to go back to

Glenn Rock. I told them that I loved teaching and I

called the borough, and they said, "What grade level are you interested

in?" And I said, "Do you have anything available?" And they said,

"Yes, but

what grade?" They said, "We can't find your application, but why don't you

come in for an interview?" I went in. Dr. Clausen was the superintendent; he was one of the best that I've worked with,

and I've worked with the lot, the good, bad, and the ugly. But he was there, and

he interviewed me, and he offered me the job. I was delighted now that I had

a job here. What I didn't realize then was that I wasn't in Freehold Township, I

was in the Boro, and I was in the ghetto school that has since been torn

down. It was built in 1865 Hudson Street school in Freehold; the

new addition went up in 1916. And to join those two additions was a

hallway. The place leaked; it had horrible conditions. I had left Glenn

Rock, which was Utopia, our playground was by Nabisco, you had the smell

of the fresh cookies and so on, we had a huge playground

to play in. On my first day of school in Freehold, they didn't even tell me where

my room was. I asked the teachers where my room was. I had no room. I wound up teaching

in the hall that joined the two schools. Then I looked out the window in

the back, and I said, "Where's the playground?" They said,

"You're looking at it; it used to be a mudhole." They had

blacktopped it over. They were three unbelievable years. I probably

would have stayed there, because I love teaching kids, but the board

administration was so corrupt in that district at that time, it was

incredible. The man who had hired me went on to Basking Ridge, and he was

only there one or two years, and then they hired someone who was just a

hatchet man to get rid of the teachers there. That was where I became

involved with teaching leadership.

Mr. Aumack: When did you come to Freehold Boro school?

Mr. May: About 1968.

In 1968 a law was passed that teachers could negotiate contracts; before

that time, they didn't. And I was in my third year of teaching, I was

not tenured, and I wasn't really involved with the profession. I don't

know why, but they asked me if I would write the original contract there,

and another teacher and I sat down and wrote it. It was sixty some pages.

And with that, I was offered another principalship in the sleaziest manner

possible in Freehold Boro. The superintendent who was there at that time,

came to my area. I had tried to make the room look nice, but it had these

huge ceilings that leaked water down the blackboard. I brought in all

kinds of flowers and plants, and had them in the back windows. I was teaching

the kids when he came and said he wanted to talk to me. He said he had

heard about my working on this contract. I wasn't presenting it or anything,

I was just writing it. And he told me, "Obviously you're a teacher

leader in this district." Well, I never thought of myself as a leader

there, I was just writing this contract. And he said, "I want you

to know you have it made in this district and if you play it my way."

And I said, "What do you mean?" And he said, "I have a

principalship coming up that you can have, but you've got to get rid of

that contract." So in other words, you screw the teachers and then

you've got a principalship. That was basically his offer. I blew up. I

said, "I can't believe your offer." I almost threw him out and

he was the superintendent. He said, "You'll do it my way or else."

I said, "I'll take the or else because I'll be damned if I do it

your way. I can't believe you'd even suggest something like that to me."

I knew it was over. And I hadn't taught too many years or in too many

places. But I had teachers come to bat to help me. One was having a really

good second year, and he really appreciated the work. I said, "You

keep your mouth shut, you'll only get yourself in trouble trying to stand

up for me and the others too." I was fired from that district, but

I made them fire me. Because I had three years of teaching, I would not

sell out, and so I knew the gig was up. He called me in to talk, I remember

it was at lunchtime. I had to go into his office, and he said, "There's

no reason to give you a contract because you don't plan to stay with us."

I said, "Oh, but there is." And he said, "Why?" And

I said, "Because I deserve one. I've worked damn hard in this district

for three years with these kids and gone over and above board. I deserve

a contract." Then all of a sudden he began to find fault with my

teaching. I said, "What's wrong with my teaching?" He said,

"Well, for instance the way you teach reading." I said, "What

don't you like about the way I teach reading?" The year before he

had offered me the reading specialist position in the district, but I

happened to be in Europe at the time, and they needed to hire somebody

immediately. I knew that, he had told me that. They were just making things

up to find a reason not to give me a contract. I said, "Look, in

your position, you can take the best teacher and make him look rotten."

And he said, "You know that." I said, "I know that, and

you know that too." Well, in his office, he got so angry with me

that he jumped up and took off and left me sitting in his office. So then

I forced him: if he didn't give me a contract, he had to fire me. So he

fired me, and I went to the New Jersey Education Association for assistance.

I had applied to five districts, and I know every one of them today, because

contracts was such a sensitive issue at that time. But what he was doing

was union busting, and it had nothing to do with New Jersey Education

Association, it had to do with labor unions. It was kind of like 1916,

when leaders of the union were fired, and therefore the union had little

power. But I had the teacher's rights fund at my disposal to sue them.

And NJEA worked very closely with me, and we were doing it. If he did

this to me, he'd be doing it to other teachers, so I figured I wasn't

going to let that happen. In the meantime, I applied to five different

districts. I had gotten five contracts in those districts even though

he was blackballing me. In fact, the principal in Little Silver sat down

with me, and was telling me what went on behind the scenes. They wanted

to hire me immediately in Little Silver, but I had been blackballed by

the Freehold superintendent. And this superintendent didn't know how he

was going to get my appointment through the board, and he didn't want

me to sign somewhere else. So he sent the principal to Basking Ridge.

Remember I told you the superintendent at Basking Ridge was really good?

The principal went up there under the guise that the Little Silver school

was looking into the math program at Basking Ridge. So then, just casually,

he said, "By the way, we had this candidate come in, Phil May. What

do you think of him?" He said, "Let me tell you, Basking Ridge

being the kind of district it is, I don't have any openings here. But

if he were to come in here for a job, I'd find one." So the principal

got on the phone, called, and I got the contract in Little Silver. I got

a contract in all five districts. I don't know how I got the contracts,

because when they interviewed me, they asked the questions. I said, "Are

you finished? Now, I have questions for you. I don't want you to think

I'm smart or putting you on, but I'm in one of the worst teaching situations

I could ever possibly be in, and I will never be in another one."

Well, then I really grilled them. I went on forever. "What kind of

district do you have here, what kind of policy, etc." And even with

that, I got contracts in all of them. I went to Little Silver, I grew

up in Shrewsbury, so I went there. And that's where I spent the rest of

my career, about twenty-five, thirty years there.

Mr. Aumack: In

Little Silver?

Mr. May: In

Little Silver.

Mr. Aumack: Is that

school still standing there?

Mr. May: Oh,

yes. I just retired a few years ago.

Mr. Aumack: What

did you teach?

|

|

|

Mr. May teaching sixth

grade

|

Mr. May: In fact, they

didn't want me to retire, which was kind of nice. I taught sixth, seventh

and eighth. Mostly sixth, and social studies, mostly, but I taught other

things. But when I turned fifty-five, I retired. They wanted me to stay

on to sixty-two at least. They said, "You're at the height of your

career, you're in educational politics, on the top." I was involved

with NJEA. I was on the committee that did the hiring and firing of NJEA

people at the state level. I was one of the teacher representatives on

that board. I had just put on two plays for the kids, Oliver one

year, and Annie. And I loved the classes, I loved teaching them.

They asked, "Why would you leave?" I said, "I have to leave

sometime." And you really reach a point where you have so many other

interests, not that I don't love teaching. I just had so many other interests.

So I retired early.

Mr. Aumack: Are

there any other stories that you can give me about the politics of

education?

Mr. May: Yes. You've

heard how I got involved in the politics of education through this superintendent,

but I didn't learn my lesson, because when I got to Little Silver, Little

Silver had no contract, and they had said they would never have a contract

because it's just not the way to do things. Now you don't work without

a contract. But then having a contract was considered terrible and unprofessional.

In other words, you take what the board gives you. So I guess I had just

gotten on tenure, and they asked me to be on the negotiating committee.

I'd never been on a negotiating committee, I'd just written a contract,

but I knew that wasn't the way it was supposed to work. I went in there

and there were three teachers. The teacher chairing it goes in to the

superintendent with the agenda, and said, honest to God, it was like whispering,

and the superintendent says, "This one I can take care of, that one

might be a possibility, this one, no don't bring that up, it would only

upset them, now this one I can take care of." And he'd go through

and he'd cut out all things on he didn't want to address, and all you

had were the things that were nothing things. And I thought, "I can't

believe this." So we went through that year. The following year we

had a strange set of circumstances. The superintendent died. One of the

two principals in the district, and the one who was real aggressive, takes

over like a superintendent, and he wants us to go in to him even though

he is just the principal. They hadn't hired a superintendent, and he wanted

us to go in with what we were proposing to him. And I wouldn't do it.

First of all, he wasn't the superintendent. And so, I write up the original

contract again. Sixty some pages again. Two other teachers were on that

committee; I wasn't head of the negotiating committee, the other one was.

I was dropping out if they didn't present a formal contract. We got right

to the wire. We wrote the contract, had all the language, but we needed

it typed up, and this was their out. Because they didn't have anybody

to type it, they weren't going to look at it. Well, I had a law

secretary who was a friend of mine type the contract. Then I got in touch

with NJEA. The head of negotiations said, "I really want to do this,

but we just can't get it typed and get all the stuff done." That

was her out. So I showed up that night with the representative from NJEA

and the contract typed, and I said, "You're going to be delighted,

I was able to get the contract typed, we have this and we're going in."

The board didn't want to talk to us, they didn't even want to touch the

contract. John Malloy, who represented us, stated, "It's just a contract,

it's negotiated between the two of you, it's an agreement of working conditions,

it's nothing to be afraid of, just look at what it says in the first page.

Look what it says in the first page." I'm watching him, because I

knew what he was doing. Well, they were curious, so they open it up. Well,

once they opened it up, they were negotiating. We worked out the original

contract, so I guess I negotiated the original contract there in Little

Silver about twenty, twenty-one years ago. Then I was involved with the

county and the state and even nationally in education politics, and in

Little Silver, I could do negotiations or I could do grievances for Little

Silver. They were afraid if I were president I'd have them out on strike.

Things got really bad one year, really bad; the teachers didn't have an

agreement, they didn't know what to do, so they came to me, saying "Would

you take the presidency?" That was in June, and the following September

we were out on strike. But we never had to do it again. It was one of

those times when we just couldn't come to an agreement. They never thought

the teachers in Little Silver would do such a thing. I told them we were

doing it. I said, "We're not going to work without a contract, we're

just not going to do it." I really feel that even through all that,

I had the utmost respect from most of the board members, the administrators,

and the superintendents.

Mr. Aumack: Why were they so

against these contracts?

Mr. May: Because they were

a threat. School boards, administrators, and superintendents could do

whatever they wanted without them. In Glenn Rock, the first school I taught

at, I was the fair-haired boy. They wanted me to be a principal. But if

we had been under contract, you can't just single out one and send him

or her for all this special treatment, paid classes and all. Contractual

benefits in that area will pay up to maybe six credits a year. These things

you have to negotiate in, you all have to agree. That's why they were

against contracts -- because it's power. Without contracts you had nothing

to say. They had full power over you and the district. But when you put

it on an equal playing field, where the boards and the teachers hammer

out a contract that's mutually agreed upon, it gives the teachers, or

any organization, certain rights. Our big problem over the years has been

not having the right to strike. We can strike, but the board can get an

injunction to have us go back. So you have the right to strike, but you

can't use it. And that's the bottom line, the board of education knows

that and knows that the teachers are going to be like the first group

in Freehold, that that situation in Freehold is what got me involved with

county leadership. Those strikers got the worst sentences, I think, in

the history of state educational politics. The teachers went on strike;

it was a bitter strike, and they were going to make a lesson of those

six, ten people, whatever it was, including the union president. He got

six months in jail. I mean it's hard to believe just for not working.

I went to college with one of the women, and that's what really got me

involved personally. She was one of the negotiators and they threw the

book at her. I don't know what they got, six weeks, whatever the term

was, but just to make it more embarrassing, she had to have surgery while

she was in jail. Well, when they took her from the county jail, they put

her with the worst criminals, they took her from the county jail to the

doctor in a paddy wagon, handcuffed. Not a nice scene. So she had the

scars from that, and she always will. She was able to overcome a lot.

And she wasn't the only one, they all got it. The men had it the easiest.

They were allowed to teach the inmates. But the women, and this one particular

one I went to school with, were not. She had had a big student, a Black

girl, in one of her classes, and when she first had this student in class

she was kind of scared of her, because this woman is small, and this young

girl was big. She had had one child at thirteen or fourteen, another one

at fifteen by an uncle, and she was tough. Well, when Lynn went to jail,

they put her in a cell with this student. Lynn was petrified as to what

would happen to her. But as it turned out, the girl happened to like Lynn,

and saw that no one hurt her while she was in there. But it could have

been the other way around. That was what they did. The right to strike

is still an issue, because the boards can get an injunction, and if you

continue to stay out you're subject to all sorts of fines, jail, and so

on. So all the board has to do is hang on long enough, and drive you to

the wall. You're not going to win. It's like boxing with one hand behind

your back.

Mr. Aumack: All right,

let's talk about Asbury Park.

Mr. May: Asbury Park?

As a child growing up I went there to the amusements and to the business

district. We went shopping in the business district, maybe once a month

with my mother and father, if you could get him to come down and do some

shopping. In the summer time, the boardwalk was unbelievable. My mother

and father would bring us down there for fireworks, for the rides, or

for whatever. Not for swimming; we always went to Seabright to swim because

Seabright was the closest beach. But for the special boardwalk, Asbury

Park was it. And the Monte Carlo pool. I mean they had the best of everything

there in Asbury Park. Beautiful area, beautiful homes, well-kept, nice

city, as far as stores and commercial area. But when I got into my first

year of teaching, which was in Wall Township, I rented a house here in

Ocean Grove. I had always had ties here in the Grove, but I was never

here very much. I came to visit. But during my first year of teaching,

I rented a house over on Embury Avenue, and was here for that year. I

used to cross over the bridge to work. I used to walk to work, because

the gift shop I had a job at was in Asbury, right across the street from

Steinbachs. During that time the Monmouth Mall had opened up. The mall

was the first thing that really dented the business district of Asbury

Park. I remember Mom driving around and around forever, looking for a

parking place, but when the mall opened up, you had all the parking you

wanted, and also the big stores. So Asbury Park lost a tremendous amount

of business when the mall opened. But what happened next really finished

Asbury off, and that was the race riots. There was a sort of like ghetto

type area here on Springwood Avenue. Lake Avenue goes into Springwood

Avenue. There was a section there that had stores and so on, but they

also had prostitution and drugs, and all kinds of things going on that

street. I never really got beyond the first or second store, but I knew

that those things were going on. Springwood Avenue goes into West Lake

Avenue, too. At one time, they changed the name of it. But then they went

back to the original, and I see as I went down that road a week or so

ago, it's Springwood Avenue. But there were a lot of Black businesses

as well as White, and most everything on that street was controlled by

White slumlords. And they got all the money, and the area got the crime

and corruption. So the African Americans who were there finally just had

it up to here. There were riots all over the country in the 1970s. I was

in the gift shop when the police came; it was like a police state, they'd

come up, and one business after the other was leaving the area. This business

that I worked for was started by German immigrants. The son was a friend

of mine. He's in his eighties now, and he took over the business with

a partner, and then I worked for them. So it was a business that had been

in the family since the turn of the century. The police came in and told

them to pull their window in every night. They had just taken over a week

to put a window display in, and I remember they had this big beautiful

American Eagle made in Italy. It was a Majolica type, it was gorgeous,

and they had it on the turnstile, and the police come in after they had

just finished and say there was a possibility of riots at any time and

we suggest you pull your window in every night. It had taken them a week

to put it in, and I remember the frustration of the owner: "We'll

just have to take our chances, we're not pulling the window in."

But after the riots, they moved out of town. I happened to have a friend

of mine who was African American, and lived in Monroe Towers over here.

The first and only time I went there for dinner happened to be the night

of the big fire in Asbury Park. We were up high on Monroe Towers, which

is one of the apartment buildings here, and we heard all this commotion

and noise, and fire trucks, and we went out on his porch. He had a porch

overlooking this. We literally watched them burn Springwood Avenue. I

mean the fire started, and they tried to contain it before it got to Cookman

Avenue, and they were able to, but it was just police, firemen, everywhere,

and fires up and down the whole street, burning the whole place down.

Black businesses and White businesses went, because once it started, everything

went. So that was the demise of Asbury and now today I'm working with

Asbury Park quite closely because Wesley Lake borders Asbury Park and

Ocean Grove, it belongs to both. About five summers ago, it was an extremely

hot summer, and nothing had been done to that lake since Asbury Park went

downhill. There was no more commercial value to the swan boat, the rides,

the merry-go-rounds; one by one, they just went. The lake itself has been

abandoned. On a good day, the western end was about six inches. Usually

it was a mud flat with garbage just strewn all over it, and this particular

summer was so hot, it was just incredible. The pondweed with all the garbage

collected in it, and the rats are swimming - it was just awful here. So

I started a group. I decided I was doing something about it. I was going

to run for Township Committee because none of the Township Committee wanted

to do anything about it, so actually I did run for Township Committee,

as an Independent, on my own, and both the Democrats and Republicans wanted

me to get off that ticket. They were both afraid that I would win. Attention

was paid to the lake. Not so much financial, but I got appointed to the

West Lake Commission. I joined that in August. They met every three months,

and I had about ten motions to make. I had my three friends with me that

I had started this group with. It's called The Citizens for West Lake.

Now there's about five hundred. In the beginning I brought all the ones

I could get to the meeting. Now I was on the commission. I had ten motions:

I made the first one that we meet every month because of the severe problems

we have. They said they don't have any money. And I said, "You only

meet when you have money? You're not going to get any money; you may as

well as not meet at all." Well, they voted that down. Then we met

at five thirty, and I said, "That's not a time to have a meeting

when you're really serious about doing something, because people are eating

at that time." I made a motion that we meet in the evening. Well,

they voted that down. My third motion was that for the next meeting, we

meet at the lake site, walk around the lake, and develop short and long-range

plans. Well that was it. I couldn't even get a second to that one! The

mayor was running, and he was from this area, and my friends said, "You

don't even care?" Well, he said, "I'll second it." Well,

they voted that all down, too. And then they called the meeting off. That

was my first meeting. They met again in December, and none of them showed

up in December. In January, guess who was left on the committee? Me. So

I had seniority, and I was chair of the committee, and we had a whole

new committee of the people from both towns and I've been working with

the citizens for West Lake in that group ever since. While I was chair,

I made the Citizens for West Lake a subcommittee of the West Lake Commission.

And then I got out as head of the Citizens for West Lake, because I'm

talking to myself being both chair of the Wesley Lake Commission and the

head of citizens for Wesley Lake. I'm still involved with it, still on

the executive board and I'm still on the commission. We've been very successful.

We dredged the Western end of the lake. Once I got a call from the state

saying that an anonymous donor had donated fifty thousand dollars, telling

the state to call me and find out where I wanted it used. I don't know

who the person was, but it must be somebody who knew me. And that money

combined with state money gave us the funds to dredge the western end,

so now instead of a mud flat, it is four feet deep. They still don't take

proper care of it, we're still have to be on them, but at least it is

four feet deep there now. And then we have the next step planned: fountains

in the center here, and on the western end. And we're moving on that.

My involvement in Asbury Park over the years has been working there, and

going there for the amusements and the business center, and now working

on the lake here which borders the two towns.

Mr. Aumack: So it seems that

you made all this work towards saving one small part of Asbury Park, and

it seems that no one wanted to help.

Mr. May: Not in

the beginning they didn't. But once I got the new board, I was chair of the

Wesley Lake Commission for two years. Then I worked to get Asbury Park

involved, so my vice-chair was from Asbury. I wouldn't take the chair without the

vice-chair being from Asbury Park, and I met with him every month. He

didn't make many of the meetings, but he made a lot of contributions. I met with him,

we did the agenda, we got to the

point where we were going out to lunch doing the agenda. Then the

head of public works in Asbury Park got on the board, and it was wonderful, so I dropped out as chair.

He's been the chair of the West Lake

Commission now for two years. The first year he wanted me to take it. And he even tried a fast one when I

called for nominations, because I was chair and nobody was going to

nominate anybody so I had to stay chair. I said this wasn't going to

work. So I told him I'd be vice-chair, and now I'm a member at large on

the committee. As a member at large, I wasn't appointed by Neptune, I

was elected by Neptune and Asbury Park to be on the commission, which was

nice. I like that because both groups were interested in my staying on.

So there's been a lot of support, although originally it wasn't easy to come by. Nobody was

interested.

Mr. Aumack: What do

you think the difference was between the second go around as opposed to

the first go around? Was it just different people or different times?

Mr. May: Different people.

People make the difference. They're pushing their interest. I mean the

first ones were waiting for the state to give them money and then they'd

spend it, that was it. And state's not giving anything, federal government

wasn't giving anything, so why meet? I hate to say it, but it was like

the good old boy network: it looks good on your resume to be on the Wesley

Lake Commission. But it has moved forward, and we've got a very active

Citizens for West Lake group and the West Lake Commission has moved forward.

Then I heard about a woman who was having trouble with Exxon, out by Dunkin'

Doughnuts here on the corner of 33 and 35, because they had a station

there that had a gas spill, and she was complaining about a cancer cluster

and so on. Well, I didn't know what a plume is, I didn't know any of this

environmental jargon, but anyway, plume is the direction that this leak

has taken. The gas was moving towards the lowest level, which would be

Wesley Lake. Well, it would take forever for it to get here, but it was

nevertheless moving in that direction. She wanted it cleaned, so I teamed

up with her and we had our first march. We called it the Plume to the

Flume March. So we met over there, we marched from Exxon down here with

a group of people; we marched to Founders Park in Ocean Grove, and that

was kind of like the turning point. Then it became fashionable to defend

the lake. The mayor of Neptune has a charity ball, and they pick a charity.

Where does the money go? To the Citizens of West Lake - and we got about

ten, twelve thousand dollars from that charity ball. And now people are

still interested in what's happening to the lake.

Mr. Aumack: Let's

go back to the race riots. Can you talk more about the causes?

Mr. May: I taught African

American history for about twenty-five years. I got a federal grant when

all this was going on. I started teaching in Freehold Boro in a ghetto

school, and the majority of students, probably sixty to seventy percent,

were African American. They had nothing in the way of African American

History. There was no history, nothing for them. It wasn't like somebody

told me they should be having a course in Black history, I just thought

these kids should have it. I never had Black history in school, if they

taught me any, I was probably daydreaming, but it would probably have

been about George Washington Carver because he was a scientist and a great

man, or Booker T. Washington. Booker T. Washington was a black leader

who did what the white people wanted him to do. I'm not saying he was

a sell out, because at that time he was able to accomplish a great deal

for his people. But he had to agree that races should be segregated. He

agreed with that. But I would get a book, it was called Proudly We

Hail. I would read to the kids when we had a lull. I'd read about

a famous Black person, and so on. Where I grew up it was all White in

Shrewsbury. I taught to Little Silver, it was all White, too. Red Bank,

where I went to high school, is mixed, so when we went to high school

it was mixed. But we never had Black History in Shrewsbury, and I came

from the same kind of district. And so I applied for a grant to teach

Black History. I developed a ten week unit that I taught every year on

African American history. You ask, what caused the race riots, there were

many things, but it was simply that enough was enough. It was the right

time and the right leadership. If you didn't have a Martin Luther King

there leading and other people like him, then I don't know whether the

Civil Rights movement would have taken off then. The segregation issue

would have taken off eventually. It had been an issue for years, but it

was like the right time, the right moment, the right leaders, to do this.

President Harry S. Truman was the one who really started the idea of integration.

During World War II , there were the Black units and the White units.

The races were not even mixed in the military. But President Truman integrated

the armed forces. As president of the United States he could do that.

So that integration in the armed forces was a step. And then in 1954 the

Brown vs. the Board of Education decision came out and was supposed to

end segregation in schools. And meanwhile the right wing bigots were fighting

integration in the military, fighting the school integration in all kinds

of ways. Governor Wallace was trying to say we're not going to integrate

the schools here in Alabama, but in 1963 the Civil Rights Act was passed

and that ended the segregation in everything. It's interesting that all

three branches were involved: one was a presidential decision, one was

a Supreme Court decision, and the other was by vote of Congress. The Civil

Rights Act passed. So you had all three branches working on this, but

that didn't mean the people wanted to integrate. So then came the fight.

You had the laws and the books, but then you had the fight for the integration.

And that created the riots, and sit-ins, and wade ins. The beach between

Asbury Park and in Ocean Grove is not a common beach. I think it belongs

to Asbury, I'm not really quite sure, but there's a beach at the end of

Wesley Lake, that was a "Black beach," that's where blacks could

swim. But that's also where the sewers emptied into. With the civil rights

movement there were many, many new ideas and laws, and of course, they

triggered the riots. And you had the leadership. It wasn't just Martin

Luther King. Black leadership started in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, but

now it had the legislature and decisions, and the leadership to implement

Civil Rights. That is the race riots as I see it.

Mr. Aumack: Was

there a growth of African Americans moving into Asbury Park?

Mr. May: Blacks had

been there for many years. Asbury was a very wealthy city, and it needed

workers in the hotels and the homes and so on, and Blacks were there,

just as they were in Glenn Rock in Bergen county. I wasn't even aware

of that because it was not my neck of the woods. And in Red Bank, the

same way, the Blacks were literally on the other side of the tracks. And

I'm sure since then there has been an influx because as people move out,

more move in, and the Blacks are in Asbury more and more.

Mr. Aumack: Let's

talk about Ocean Grove. Tell us about

the Pine Tree Inn.

Mr. May: In teaching

it's not true that you get paid twelve months a year. You get paid ten,

and you're unemployed for two. So you look for another job or spread your

money out over twelve months. I had taught summer school and those things.

I've always had ties here in Ocean Grove and I liked it enough that I

really wanted to buy something here, but I had a home up in Tinton Falls

on Sycamore Avenue. I thought it would be different to have a bread and

breakfast rather than teaching summer school every year. I always like

to try new things. So I thought I'd try a bed and breakfast see how that

worked out. The Pine Tree Inn came up for sale and my partner and I purchased

it, but I ran it during the summer. And I started the inn. The woman we

bought it from had a dinner at the end of the season on Labor Day weekend.

She invited my partner and me to meet the people who were there. One lady

with her cane came over. She was ninety years old, and she said, "I

hear you went to Montclair." And I said, "Yes, I did."

And she said, "I went there, too." I said, "What year did

you graduate?" And she said, "I graduated in 1911." I said,

"1911; that was the first class!" She said, "Yes I was

in the first class that graduated from Montclair." And it turns out

that she and her two sisters were great nieces of President Cleveland.

They were actually those three and their brother. But the brother didn't

come with them. But one sister was ninety, one was eighty-eight, and the

other was eighty-six. And the last time they came to the Inn they were

about ninety-six, ninety-four, and ninety-two. And the brother was still

alive in his late eighties. They were wonderful guests. I ran the hotel

summers, then, because I love doing places over, I did the whole thing

over, and, in fact the place was in Country Living after I finished

it. I sold the place in Tinton Falls and I moved to the Pine Tree Inn.

Now I was back living in the Grove again, always getting involved in things.

I was on the Executive Board of the Historical Society at the time and

I also had my real estate license in town, and I also had, since I had

the hotel, membership to the Hotel Association. I was treasurer of the

Hotel Association and in fact one of the founders of the Chamber of Commerce

- founded the Chamber of Commerce in this town. I founded the Citizens

of West Lake Group, too. So I had the Inn for about seven years, and the

problem is, I'm not an absentee landlord and I had problems. I never had

a break and was working fourteen months a year because in the fall I was

starting the school year off and closing the hotel which is like double

work, and in the spring I was opening up the hotel and closing out the

school year. So it was like round the clock work. I wanted to make a private

home out of it, but I thought so much of the guests I didn't really want

to tell them they can't come anymore, so I sold the hotel and I moved

to Interlaken. Interlaken is just a mile from Ocean Grove; it's on the

other side of Asbury Park, a lovely community. But in many ways afterwards

I wished I had kept the Pine Tree because the new owners were terrible,

and the guests never came back again after they came back that year and

left early. Interlaken was wonderful, but the Grove is really unique.

It not only is a National Historic Site, it's between two lakes, Wesley

Lake, that I'm on, and Fletcher Lake on the South end, and the Ocean to

the east. So it's a very small area, about a half a square mile, but a

tremendous amount of the work here is done by volunteers. There are many

different volunteer groups in town. And when you come from this kind of

environment and you go to Interlaken where everything is just wonderful

but was also kind of boring compared to Ocean Grove, so I bought this

beat up old house in Ocean Grove. I did it over, I furnished it, but I

never lived in it, never even spent a night in it, but I had it on the

Christmas house tour, etc. People used to call it my doll house. Eventually

I sold it, and then this place came up for sale, and what I liked about

this was the size of the property. Ocean Grove was like house, alleyway,

house, and alleyway all very close. But this house had property, and it

was a big house. I was just going to buy it; I still wasn't going to leave

Interlaken, and I was just going to buy it, make some changes, and then

resell it. Well, I got into it; I designed the whole thing, did the whole

thing over, put in new ceilings, did the wallpaper, and everything, even

the kitchen and the bathroom. And I moved in. I was no sooner back in

the Grove when I was asked to take over the presidency of the Historical

Society. And meanwhile I was president of my local in education. Local

presidency of all the educational things is very difficult, because you're

negotiating contracts, you're negotiating salary, doing some work with

salaries, grievances, and so on and so forth. So I was president of the

local, I was president of the county, and I had ten thousand members,

and I was president of one or two other things, I had five other groups,

and then they were asking me to be president of this historical society.

I said, "Well, I want to know everything that happened since I left."

Anyway, I took it. You could only serve a limited term, two years. Anyway,

they changed the constitution and I've been the president ten years. And

it's election year and I'm still trying to find somebody else to take

it. But anyway, when I took it over, we were a little hole in the wall

behind the bank over in town. The place took every bit of money we had

to rent it, and we couldn't even put our stuff in it. We made a move here

probably about five years ago. We moved into the Ocean Grove Camp Meeting

Association lobby, because they had a CEO there who they had hired who

was really good and interested in community involvement. They put out

a notice to all the organizations that if they'd like to be a part of,

or have a desk in the Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association office so that

they could work together on common issues. No one responded but me. I

didn't want a desk and phone, I wanted the whole lobby plus a desk and

a phone, and I got it. And then about four years ago, we bought a collection.

We had to take the whole collection, and a lot of it had nothing to with

Ocean Grove. It was Asbury Park stuff, Avon, you know, shore community

things, but we had to buy the whole thing, and it was very expensive;

it was around thirteen thousand dollars. And we had no place to store

it, and really had no museum of our own. We were saving to buy a museum,

and if we spent the money, we wouldn't have it for the museum. I had the

deciding vote; it was nine to nine, so I had to break the tie, and I said,

"Only if we buy it, we get rid of everything that has nothing to

do with Ocean Grove." So we had an auction. Incidentally, that auction

was the first of several. We just had our fourth annual auction last week.

That first one was really a hoot because I did the auctioneering, and

I had never done that. But we made twelve to thirteen thousand dollars.

We made enough to pay for the whole collection and we have what we wanted

out of it. If you go out past the auditorium, you'll see the historical

society straight ahead of you. When the building came up for sale, it

was a kite shop and filthy and run down. The basement was so littered

with debris and garbage and busted bricks and dirt that they thought it

was a dirt floor. It took six months to negotiate the deal, but we did.

Then we didn't have any money to fix it up. We only had about three or

four thousand dollars, and that was only enough to clean the rugs and

paint and put all our stuff in. And the rugs were awful. So I put out

an appeal to friends and members, and so on, to be a founder of the new

museum. If they give twenty-five to ninety-nine dollars, they'd get on

this list, and so on and so forth. And I was very fortunate, because the

executive board voted that whatever money we got we could use it to put

the museum together. So I didn't have to go back to them for each expenditure.

Well, the money came in and although I had never done fundraising before,

we took in about fifty thousand dollars. The museum now looks wonderful.

Not only upstairs, but downstairs as well. We have a new cooling system,

and a gallery. So that has been my involvement with the historical society.

Now we're involved with the end of Main Avenue where there was a statue

called the Angel of Victory statue that was put up in 1878 to commemorate

the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Monmouth. This was kind of

interesting because the Civil War had just ended and Ocean Grove was only

nine years old. The statue was ten feet and the base was eight feet. In

1922 it had troubles with the metals it was made of. The lead corroded

within itself and it collapsed in a storm or something. So anyway, recreation

of this statue is something that we'd like to. We can't restore it, but

we'd like to recreate it. That's one of the main projects we're working

on now. But as you can see, I'm very much involved with the town here.

And what are some other questions that you have?